A Discombobulated Regiment

During the winter of 1861-62, any number of battlefield disasters in the Confederacy, caused the War Deptartment to call upon the states to furnish additional regiments of all arms to be rushed to various fronts to forestall a forced reunification of the states. Out in Texas several infantry and cavalry regiments underwent hurried organization: This included the 6th and 10th Texas Infantry, and 15th, 17th, 18th, 24th and 25th Texas Cavalry. When the Sec. of War ordered the Dept. commander of the “Lone Star” State to furnish fifteen regiments, of which this seven would constitute the largest segment. Ordered to Arkansas and Mississippi, the latter didn’t transpire because the U.S. seized the various crossings of the Mississippi River; leaving these regiments to initially see service amongst the citizens of Arkansas, which the Texians often derisively referred to as “rackensackers.” The infantry commands enlisted for three years (or the war), while the cavalry joined up for just twelve months! While the former mostly had uniforms and military arms, the latter mostly entered the service supplying their own mounts, tack, clothing, etc. The infantry had several months of military discipline exposure, while the cavalry seldom knew more than a very limited amount of drill before going off to fight.

In Arkansas the cavalrymen of the 15th, 17th, and 18th Texas, unfortunately, were the first to “smell smoke,” these being small unit attacks upon Union troops in the northeast who were steadily pushing south in an effort to take Little Rock; knocking Arkansas out of the war. By mid-July, these regiments had accomplished their mission and were moved to just east of the capitol. But as with the other new regiments reaching Arkansas, diseases, and infirmities had already made huge inroads in reducing these regiments, who suffered from poor rations, and scant medical care upon becoming sick. The 15th, 17th and 18th Cavalry were now thrown into a brigade centered on the well-drilled 10th Texas Infantry. Then, to the mortification of the cavalrymen, they were dismounted, their horses sent home and their service extended to a full three years! Additionally, all men over 35 or under 18 were discharged under the first Conscript Act; the regiments all reorganized, and to make matters seemingly worse their pay was reduced to that of their web-foot counterparts!

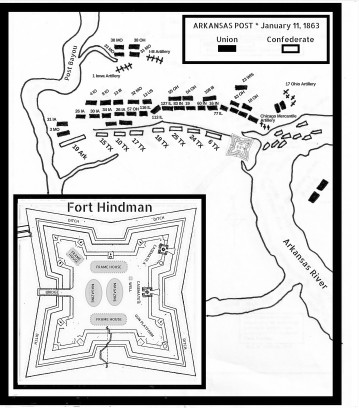

About this time the veteran 6th Texas Infantry had been halted outside Pine Bluff, where they began to drill anew, where it was joined by the 14th and 25th Texas Cavalry (the latter had been ordered dismounted as well), and the three commands organized in a second Texas Brigade. It was charged with preventing the enemy’s employing the nearby Arkansas River as a means to send naval gunboats and land forces up to reach Little Rock from the southeast. As had their counterparts near Little Rock, these new cavalrymen had likewise struggled with their share of mumps, chicken pox, and Small-pox. Many a man went home feeble, never to or worse, went into shallow graves that surrounded their camps. In September this latter brigade moved by forced marches downstream to Arkansas Post, just back of the Mississippi, where a military post (dubbed “Ft. Hindman) had undergone construction. Surrounded by swamps and exposed to millions of mosquitos, not surprisingly, sicknesses proliferated. In late November they were joined at the Post by the remaining, by now fairly-trained infantry brigade that incorporated the 10th Texas Infantry, and the 15th, 17th, and 18th Dismounted Cavalry.

Arkansas Post

As Volume I of “A Force:” covered extensively the resulting Battle of Arkansas Post, this piece will focus on the consequences of that fight. One entire company of the 17th Texas Cavalry Dismounted had been out as skirmishers down Post Bayou and escaped completely the debacle suffered by their comrades. They were joined for many days thereafter by soldiers from the 6th and 10th Infantry, and 15th, 18th, 24th and 25th Cavalry Dismounted. Some had gone back to Little Rock, but a plethora returned to their Texas homes. Throughout the spring of ‘63 the various complements of men were temporarily organized and ordered to camps before being ordered in early summer to Shreveport, La. On July 1st, these survivors were enrolled in the newly created 17th Texas Consolidated Dismounted Cavalry, with Col. James Taylor of the 17th selected to command the regiment (of just eight companies), two days later receiving a presentation flag presented by Miss Emma Watson.

Here they were re-brigaded with the 22nd and 31st Texas Dismounted, and soon after by the 34th Texas Dismounted. Following several months of intensive drill, the brigade gained a new commander in the form of a diminutive Frenchman by the name of Camile Armand Jules Marie, Prince de Polignac. The Texans noted his short stature and, coupled with the fact he spoke French more often than not, designated him their “Polecat.” They were ordered to Alexandria, where they entrenched that city, where they were to be supplied with “Enfield and Springfield rifles and accoutrements” recently captured from the enemy recently at Brashear City. The brigade reached Maj. Gen. Richard Taylor’s army in late October 1863, to serve alongside Taylor’s former brigade of Louisianans. After a mid-winter campaign to northeast Louisiana, many men having no shoes (and Pneumonia taking many lives), the brigade returned to Taylor’s army near Alexandria, reaching Pineville on March 14, 1864. Here they entered into the west Louisiana “Red River” campaign that would witness them achieving perhaps the most significant victory over the enemy they were to experience.

Polignac’s and Gray’s La. Brigade became a new division, during which time they retired northward through Ft. Jessup, reaching Pleasant Hill On April 1st. On the 3rd the brigade made it to within six miles of Mansfield, a day later marching through and beyond the town where they rested several days, awaiting reinforcements from Texas. On the 8th, the army marched back through Mansfield, their band playing “Dixie.” Then continuing southeast three miles to reach the Sabine Crossroads, the band struck up the “Bonnie Blue Flag,” the martial music signifying the opportunity had arrived to “see the elephants,” as the soldiers realized they were about to fight. Turing their column to the left and moving north, they were halted and the La. Brigade moved beyond them to become the new left flank (Texas Confederate cavalry brigades would be advanced to their left thereafter, all to take their guide from Taylor’s army.) Near 4:00 P.M., Taylor road past Polignac, calling forth: “Little Frenchman, I am going to fight (Maj. Gen. Nathaniel) Banks here if he has a million men.”

Having been moved to a new position just north of a rail fence that ran east and west, the division was ordered to advance in-echelon, left in front, which would see Polignac’s Brigade strike the enemy’s troops posted behind the fence, it turning out that the 17th Texas Consolidated confronted the 130th Illinois Infantryof Brig. Gen. Landrum’s 13th Corps Division. Here the enemy line had turned south and the right wing of the 17th Texas exploded through the interval between the 130th and the 77th Illinois on the former’s left. Maj. Gen. Alfred Mouton having been already been killed, Polignac assumed division command, with Col. James Taylor of the 17th taking over “Polecat’s” Brigade. The latter had already lost Lt. Col. Sebron Noble, killed early on in this charge, Maj. Tucker taking over the regiment. The 17th Texas pivoted upon its left flank to the enfilade the ranks of both the 49th Ohio and 19th Kentucky Infantry from the rear. Sweeping everything before them, the Texans next struck a second line of the Federals a couple of miles beyond, capturing artillery, wagons, and hundreds of enemy soldiers.

Near dark, three miles further along, the winded Texans struck a new line composed of troops from the 19th Corps, which had been rushed forward to stem the rebel advance. Struggling to drive the enemy away from the only fresh water available to the adversaries, Col. Taylor of the 17th Texas led the men in a final charge but was shot dead in the melee near the water course. A post-event analysis of the casualties in the regiment noted twenty-three killed and forty-five wounded. Among those killed in the initial charge was Lt. Jose de la Garza, formerly of the 6th Texas Infantry, who apparently died along with five others in the explosion of a shell which struck the regimental colors as they moved across the field in front of the fence. Afterward, the brigade withdrew to their former camps above Mansfield, where the men of the 17th received issues of Federal canteens, cartridge, and cap-boxes, bayonets, and belts from the immense trove of material that fell into rebel hands.

The brigade was again called to the front the following day at Pleasant Hill, and while they saw some action, it was minor when compared to the previous afternoon. The colors of the 17th Texas Consolidated Cavalry was brought back t Texas at war’s end and ultimately preserved by Ensign W. H. Parker, who had borne it through the war. The September 1903, Athens Review, carried an article written by a Dallas newspaper reporter Dallas who traveled down to the parson’s abode to view it and get the story behind it.  And that very same flag made an appearance at the 1929 reunion of the regiment in Lufkin, where an image was made of Capt. Fears of Co. A, 17th, along with Ensign W. H. Parker holding it aloft. One can clearly observe the bullet and shell piercings still present across its face after all those years. Dismounted cavalry units from Texas made up a large proportion of the infantry commands that served in that deadly conflict and for that reason, their stories need to be related to every generation that considers themselves to be “real Texians.”

And that very same flag made an appearance at the 1929 reunion of the regiment in Lufkin, where an image was made of Capt. Fears of Co. A, 17th, along with Ensign W. H. Parker holding it aloft. One can clearly observe the bullet and shell piercings still present across its face after all those years. Dismounted cavalry units from Texas made up a large proportion of the infantry commands that served in that deadly conflict and for that reason, their stories need to be related to every generation that considers themselves to be “real Texians.”

Recently Danny gave a talk on this subject. A video of that presentation can be found here:

To see the maps and images, you can explore his presentation here: 17th Texas Presentation